Enforcement of Tobacco Control Laws in Kenya

The only measure for which Kenya is recognised as having attained the highest level of achievement in terms of compliance is tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship.

The tobacco control measure with the lowest level of compliance in Kenya is the ban on sale of single cigarette sticks.

Kenya ratified the World Health Organization (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) in 2004. The WHO FCTC is the first international agreement to address the issue of tobacco use.

Following the FCTC ratification, Kenya adopted its first Tobacco Control Act in 2007 and Tobacco Control Regulations in 2014.Compliance refers to the fulfillment of tobacco control obligations/requirements by members of the public, tobacco industry players, and other regulated entities.

Enforcement refers to the measures that the government takes to ensure compliance, including actions to prevent/deter offenses and respond to breaches of the law. Enforcement is often a series of escalating interventions/sanctions, starting with persuasion, warnings, civil penalties, criminal penalties, license suspension, and license revocation.This page provides information about the degree of enforcement in Kenya, the level of local compliance with existing tobacco control laws, and the successes and challenges with enforcement.

Kenya has adopted various tobacco control policies to fulfill its obligations under the WHO FCTC, as outlined in the timeline below.

The FCTC obliges Parties to adopt tobacco control measures, including:

- Prohibitions on tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship

- Protection of individuals from secondhand tobacco smoke

- Implementation of higher tobacco taxes

- Placement of graphic health warnings on all packages of tobacco products

- Prevention of sales to and by minors

- Regulation and disclosure of product contents and emissions

- Provision of tobacco cessation services, and

- Promotion of alternative livelihoods for tobacco farmers.

Note: This timeline does not contain information on changes to tobacco tax and illicit trade policy. These are contained in the Tobacco Tax Page

In November 2014, the tobacco industry filed a lawsuit challenging the Tobacco Control Regulations 2014. The regulations were subsequently suspended pending the hearing and determination of the lawsuit. In September 2016, the regulations dealing with PHWs were partially implemented (three out of 15 PHWs), with another three warnings implemented in 2018. In November 2019, the litigation was dismissed by the Supreme Court, thereby allowing for full implementation of the regulations and remission of the 2% solatium compensatory contribution.

Enforcement Infrastructure in Kenya

Article 5 of the FCTC mandates a comprehensive multi-sectoral approach to the implementation of tobacco control measures. This requires high level political commitment and a whole of government approach.

Though the Ministry of Health is the main agency responsible for tobacco control policy development and implementation in Kenya, other government agencies and departments bear some responsibilities as outlined in the table below:

| The Presidency | • Ensure and sustain high-level political commitment to tobacco control and implementation of the WHO FCTC and related instruments |

| National Assembly and Senate | • Provide political commitment and support for the adoption of effective tobacco control policies and legislations |

| Ministry of Health | Serve as the focal point for implementation of the WHO-FCTC and its instruments. This includes: • Coordinating multi-sectoral tobacco control action (serve as the secretariat for the national coordination mechanism and any Technical Working Groups (TWGs) established thereunder) • Co-chairing the National Tobacco Control TWG under the Non Communicable Disease Inter-Sectoral Coordination Committee (NCD-ICC). • Leading the development, coordination, implementation, and enforcement of tobacco control policies and legislations • Monitoring and evaluating implementation of the FCTC and Tobacco Control Act • Mobilizing resources • Facilitating capacity building for other government ministries and agencies • Establishing and coordinating tobacco cessation services • Undertaking public awareness campaigns on the dangers of tobacco use and outlining legal provisions for compliance |

| Kenya Bureau of Standards | • Contribute to the development of policies, legislations, standards, and guidelines for the regulation of tobacco products • Test tobacco product contents and emissions • Guide the packaging and labeling of tobacco products |

| Ministry of Investments, Trade and Industry | • Monitor and provide information on tobacco trade and related activities • Protect obligations to the WHO FCTC in bilateral and multilateral trade and investment agreements |

| Attorney General | • Provide legal advice on the development and interpretation of tobacco control legislations and regulations • Provide support for enforcement of and/or compliance with tobacco control laws and regulations • Protect obligations to the WHO FCTC in bilateral and multilateral agreements • Provide support in negotiation of further FCTC Protocols |

| Ministry of Foreign Affairs | • Monitor and provide information on bilateral and multilateral agreements affecting tobacco control • Facilitate ratification of the WHO FCTC and its Protocols • Provide support for compliance with requirements of the WHO FCTC and its Protocol, as well as regular reporting |

Source: WHO Regional Office for Africa 2015, National Coordination Mechanism for Tobacco Control: A Model for the African Region, as supplemented with roles of the respective Ministries from their websites.

The Tobacco Control Act and the 2014 regulations provide for the following enforcement officers: public health officers appointed under the Public Health Act (Cap. 242), medical officers of health, customs officers, police officers, administration police officers, prisons officers, local authority inspectorate officers, and Kenya forest rangers. These officers have the power to enter any place where tobacco or tobacco products or any ingredients used in their manufacture or any information related thereto are produced, manufactured, tested, packaged, labeled, promoted, or sold. They also have the power to inspect premises, examine, test, seize, and store any articles they suspect have been used to commit an offense, and arrest and prosecute individuals for offenses under the Tobacco Control Act.

Best Practices in Enforcement

Enforcement of and compliance with tobacco control legislation is informed by: the FCTC, the FCTC Guidelines adopted by the Conference of Parties and other relevant decisions of the Conference of Parties, domestic tobacco control laws, and other domestic laws on civil and criminal procedure.

An effective tobacco control enforcement mechanism has several characteristics

:Coordination and clarity of mandate

Effective coordination and clarity of mandate between various enforcement agencies

The structure of the tobacco control enforcement mechanism should be defined in the law, should state the enforcement agencies and their roles, identify the lead agency, have clear terms of reference for the structure and for each enforcement agency, and specify the funding mechanism for enforcement activities

Enforcement action plan

An enforcement action plan

:This plan should delineate the various entities within an inspection area that have obligations under the tobacco control laws. It should also define inspection priorities and state the number and types of spots to be inspected (e.g., entertainment spots and workplaces should be inspected to ensure that they are smoke free, while retail spots should be inspected to verify that advertising/billboard bans are being followed).

The plan should assess what inspection resources are required and specify the agencies that are to provide them. It should identify the authorizations that need to be obtained (if any).

Adequate resources

Adequate human resources, budget and tools of work

Enforcement agents should receive adequate and regular training in various domains, including communication and stakeholder engagement, enforcement information management systems, and product surveillance (such surveillance will allow them to keep pace with novel products emerging in the market). Agents should also be trained on relevant laws (tobacco control laws, laws governing searches, seizures, and preservation of evidence, and civil and criminal procedures).

In addition, agents should be trained on how to testify in courts and other administrative tribunals.

Compliance promotion

Compliance promotion

These are activities to raise awareness of the new legislation and obligations among the public and affected stakeholders.. Awareness sessions can be held before legislation comes into force, during inspections (when dealing with first-time violators), or at regular intervals after the law comes into force.. Mass media campaigns, organized meetings with stakeholders (such as hotel owner’s associations), and printed material distributions (such as ‘no smoking’ signs, brochures summarizing a new law, or warnings/notices for first-time violators of minor offenses) can all be leveraged to raise awareness.

Provision of information to tobacco industry players should be guided by Article 5.3 of the FCTC which limits interactions to those strictly necessary for regulation and requires such interactions to be accountable and open.

Compliance monitoring

Compliance monitoring

These are activities to determine the level of compliance with tobacco control laws and respond to violations. These activities involve identification, documentation, investigation, and response to violations. Methods of compliance monitoring include inspections conducted by enforcement officers, self-monitoring, self-recordkeeping, and self-reporting by the regulated community, and complaints from the public. Tobacco product inspections may either be routine, sporadic (i.e., without prior notice), or taken in response to reports of violations.

Enforcement agencies should establish a system of providing information from self reporting to non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and members of the public. Such a system would allow these stakeholders to scrutinize the information for accuracy/completeness and leverage it for public education and awareness campaigns.

Enforcement agencies should also create and publicize a system that allows NGOs and members of the public to report the violations they have observed or experienced. This system could include toll-free lines, websites, or the offices of specified law enforcement agencies. This system should be publicized and complaints addressed when they are raised to bolster confidence that violations will be dealt with and encourage the public/NGOs to use the system.

Involvement of Civil Society

Involvement of Civil Society in building support for and ensuring compliance with the tobacco control measures

Civil society organizations should be involved in enforcement activities, particularly as they can help build political will for tobacco control across political parties. Such organizations can be engaged to educate the public and opinion leaders on tobacco control obligations, counter opposition from the tobacco industry and its allies, and monitor compliance with the tobacco control legislation. Where the legal system allows, civil society organizations can be given enforcement or quasi-enforcement roles such as the power to initiate action to compel compliance.

Strategic approaches to enforcement

Strategic approaches to enforcement

To maximize compliance, simplify the implementation of legislation, and reduce the amount of resources needed, the following strategic approaches to enforcement should be followed:

- Provide reasonable deadlines for compliance after the law comes into force

- Start enforcement immediately after the law enters into force. Enforcement could begin ‘softly’ with a grace period that allows stakeholders to learn about the new obligations without suffering penalties. Alternatively, authorities could immediately penalize ‘big fish’ for violations (i.e., the owners of premises that allow smoking or tobacco advertising and promotion). Such high-profile prosecutions could be used to enhance deterrence.

- Utilize the public and community in monitoring compliance – encourage them to report violations

- Establish an efficient system capable of providing real-time responses to public complaints and reports.

- Utilize existing inspection systems for enforcement of tobacco control legislation

- Decentralize enforcement to the local level to increase the amount of inspection resources available and boost compliance. This approach requires the establishment of a national coordinating mechanism to ensure a consistent approach nationwide.

- Form a strong enforcement and compliance coordination mechanism within the counties that can be cascaded to all sub counties.

Enforcement Challenges

While there is strong public support for tobacco control laws, the level of enforcement by the government is perceived to be low.

Tobacco Users’ and Non Users’ Opinions about Government Responsibility on Enforcement of Tobacco Control, 2018

Over 80% of respondents to the 2018 International Tobacco Control (ITC) survey agreed that tobacco products should be more tightly regulated, while over 88% supported a total ban on tobacco products within 10 years if the government provided cessation assistance.

Despite Kenya’s adoption of tobacco control policies since 2007, enforcement faces key challenges, including industry interference, inadequate resources (financial and human), weak enforcement capacity

, lack of coordination and unclear mandates of the principal institutions involved in tobacco control efforts, and limited awareness by non-health state actors on their obligations under Kenya’s tobacco control laws.Interference from tobacco industry players is one of the key challenges hindering the enforcement of tobacco laws in Kenya. These players often challenge the implementation of tobacco control policies or use underhanded tactics like bribery to slow enforcement.

Kenya is listed as one of the countries with the highest level of achievement in enforcement of bans on tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship.

However, advertising at points of sale (through use of brand colors) and on social media platforms is still prevalent.Article 13.2 of the FCTC requires each Party to comprehensively ban all forms of tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship, including cross-border advertising. Kenya’s comprehensive ban on tobacco advertising promotion, and sponsorship is contained in part IV of the Tobacco Control Act.

In Kenya, compliance with the ban on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship increased between 2012 and 2018. In 2018, only 8% of ITC respondents noticed adverts designed to promote tobacco consumption versus 11% of respondents in 2012. However, there was some evidence that enforcement of existing restrictions needed to be greater at entertainment, media, and retail outlets. In 2018, about 22% of respondents observed tobacco use in entertainment media in the previous six months, which has been linked to youth smoking.

Respondents Who Noticed Tobacco Products Being Advertised in Various Venues by Wave

Point-of-sale tobacco advertising, including product stacking and displays, is banned in Kenya. However, a 2017 study in Nairobi, Kakamega, Vihiga, and Tharaka Nithi counties found that 392 out of 400 vendors still had tobacco product displays. These displays took various forms, including packs laid out on trays, tables, or other surfaces, organized shelves, hanging displays, or illuminated displays.

Section 25 of the Act prohibits advertising on “any medium of electronic, print, or any other form of communication.”

However, the tobacco industry has found ways to advertise products to the youth through social media sites like Facebook and Twitter. Social media is particularly used to market nicotine pouches. The social media sites do not have effective means of verifying age; they also allow for deliveries, breaching the law on sale to minors. The adverts for nicotine pouches are also accompanied by adverts and price lists for cigarettes as related products.The Act further prohibits the promotion of brand elements such as color – in other words, a cigarette manufacturer such as British American Tobacco should not project or display its brand colors in any location. However, it is still common to see brand colors in boxes and displays in roadside shops. For example, street vendors that use branded umbrellas to shield themselves from the sun may have removed or patched over the obvious textual advertising. However, the color of the umbrellas still serve as subtle reminders of what is on sale.

Despite good compliance in most public offices, government buildings, and other workplaces, smoking in public continues to be observed in the hospitality/entertainment sector. The provision for designated smoking areas weakens Kenya’s smoke-free policies and hinders universal protection against secondhand tobacco smoke.

The Guidelines to Article 8 of the FCTC

require 100% smoke-free public places. Section 33 of the Tobacco Control Act, 2007 bans smoking in public places (which are defined as any indoor, enclosed, or partially enclosed areas that are open to the public, including workplaces, and health, educational, and recreational institutions). However, smoking is permitted in designated areas. The definition of a designated smoking area in Section 33 provides for ventilation, which has been proven to be ineffective in protecting from exposure to secondhand smoke. Furthermore, the areas set aside as designated smoking areas do not meet the specifications set out in the law and do not protect the public near them from exposure to secondhand smoke.The 2014 regulations expanded the areas in which smoking is banned to include private vehicles with children on board and streets, walkways, and verandas adjacent to public places. Kenya’s smoke-free provisions are comprehensive, save for the designated smoking areas.

Respondents Who Smoked or Witnessed Smoking in Public Places by Wave

Smokers Who Smoked in Public Places

Respondents Who Witnessed Smoking in Public Places They Visited

Source: ITC, 2020

The ITC survey revealed that compliance with the ban on public smoking was high in public transport vehicles, hospitals, and restaurants. Conversely, compliance was low in bars and private workplaces. In 2012, 76% of smokers stated that they smoked in bars, whereas in 2018 65% of smokers reported that they smoked in bars. In 2012, 70% of respondents who visited a bar witnessed smoking, whereas in 2018 57% of respondents who visited a bar witnessed smoking.

Enforcement at the county level still faces challenges. In Nairobi county, the smoke-free law has largely been enforced in the central business district. However, in recreational areas such as Uhuru Park and in street markets within residential areas, public smoking still occurs during the day and at night given the absence of enforcement officers.

Enforcement at night requires presence of the police to ensure security for enforcement officers which is not routinely provided or financially provided for.A 2018 study carried out in Nakuru county found that roughly 253 out of 264 licensed liquor establishments (96%) permitted smoking within their premises. The required ‘no smoking’ signs were present in 42% of restaurants, 50% of night clubs, and 58% of bars.

Another 2019 study surveyed 384 bars and restaurants in Nakuru and Kisumu counties. The study found that smoking took place in 43% of the bars and restaurants. Approximately 49% of the bars and 58% of the restaurants did not have ‘no smoking’ signs.Though the pictorial health warnings adopted in 2014 meet the minimum requirements outlined in the FCTC, they fall short of international best practices with regard to size and rotation (i.e., different warnings displayed on different packs). Kenya ranks 128 out of 206 countries worldwide that have implemented PHWs on cigarette packs.

Cigarette Package Health Warnings Ranking

Hovering on each country will reveal the cigarette package health warnings ranking.

The lower the score, the lower the level of compliance

- Average Front/Back Score|

- 0 - 30

- 31 - 40

- 41 - 50

- 51 - 60

- 61 - 70

- 71 - 80

- 81 - 90

- 91 - 100

- No Data

Source: Canadian Cancer Society, 2023

Health warnings on tobacco product packaging are an effective method of spreading health information since every tobacco user gets to see the images every day.

Article 11 of the FCTC requires tobacco packages/labels to bear large, clearly visible, and legible health warnings. These warnings, which must be rotated, should cover 50% or more of the tobacco package. The warnings may also take pictorial form. The Guidelines to Article 11 of the FCTC recommend that the larger the pictorial health warnings the greater the impact. In addition, the health warnings should address a range of issues that are tailored to gender, age, or particular groups in the population.

The guidelines further recommend that multiple warnings should be in circulation at any given time. The warnings and messages should also be changed from time to time, and plain or standardized packaging should be considered as well.

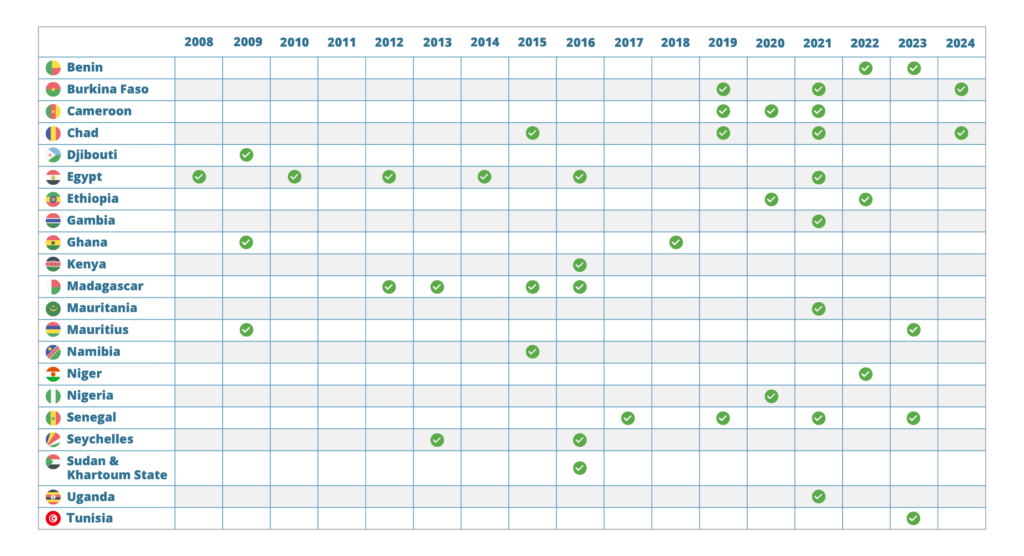

By 2018, PHWs on cigarette packs were in place in 117 countries and jurisdictions worldwide.

Sixteen African countries, including Kenya, have implemented PHWs. The 2007 Kenya Tobacco Control Act and the Tobacco Control Regulations 2014 provide for a set of 15 PHWs in both English and Kiswahili covering not less than 30% of the total surface area of the front panel and 50% of the total surface area of the rear panel, and both located on the lower portion of the package directly underneath the cellophane or other clear wrapping. In addition, the messages in circulation should be changed after every one year (12 months), with the 12 month period ending on 31st December of every year.However, due to a legal challenge against the 2014 regulations from the tobacco industry, only three out of 15 of the PHWs were implemented in 2016. An additional three of the approved PHWs were implemented in 2018 (leaving nine of the approved PHWs unimplemented). In addition to the PHWs, a textual warning sign was printed on the packs.

Impact of Kenya’s Graphic Health Warnings

Since 2007, Kenya has moved from text warnings to PHWs covering 30% of the front and 50% of the back of the surface area of tobacco packets. The initial impact of this change on smokers perceptions and behavior has waned over time,

necessitating newer, larger PHWs.In 2012, 63% of tobacco users and 90% of non-users thought that more health information should be displayed on cigarette packages as existing text warnings were inadequate.

Between 2012 and 2018, the change from text to three PHWs had an initial impact on smokers. For example, 72% of smokers in 2018 reported that they noticed the health warnings on the packs whenever they smoked compared to 64% in 2012. The implementation of PHWs also influenced the behavior of smokers. In 2018, 32% of smokers and 10% of smokeless tobacco users avoided the warnings (by either covering them up, keeping them out of sight, using a cigarette case, avoiding certain warnings, or any other means), while 26% of smokers and 11% of smokeless tobacco users had given up smoking because of the PHWs. Additionally, when compared to text warnings, PHWs proved more likely to influence smokers to reconsider the negative health effects of smoking. In 2018, 38% of smokers and 21% of smokeless users reported that they were more likely to quit.Impact of Health Warnings on Cigarette Packages Among Smokers in Kenya, by Wave

However, a review in 2018 revealed that the three PHWs in circulation had design flaws that limited their impact. Specifically, 43% of the respondents who were smokers perceived the PHWs as unrealistic or mythical, 15% described them as not convincing, and 13% said they were only meant to instill fear among smokers. Of the three PHWs in circulation, 32% of respondents recalled the images for mouth cancer, while only 13% of respondents recalled the images for cancer and impotence, respectively. Furthermore, a disconnect between the images and the messages they are supposed to convey was observed (e.g., many respondents interpreted the image for impotence to mean divorce, whereas the image for mouth cancer was interpreted as tooth decay or tooth loss and not mouth cancer).

In 2021, the Ministry of Health prepared the draft “National Guidelines for Packaging and Labeling of Tobacco and Tobacco Products.” These guidelines proposed increasing the size of PHWs from 30% on the front and 50% on the back to 80% on both the front and back panels of tobacco packaging. These guidelines have not yet been implemented. The current health warnings fall short in terms of rotation and are smaller than what is proposed in the new national guidelines. Other African countries such as Benin have health warnings covering 90%

of the front and back of tobacco products.Despite a ban on the sale of single sticks, the majority of smokers in Kenya (82%) last purchased cigarettes in loose (single) form rather than in packets.

The sale of single sticks is prevalent in many countries, especially low- and middle-income countries.

Even though section 18(1) of the Tobacco Control Act prohibits the sale of cigarettes, except in packages containing at least 10 cigarettes, single sticks are still readily available in many parts of the country.Single sticks are affordable to the youth and others with limited resources as they are perceived to be cheaper than buying an entire pack.

At the same time, traders prefer to sell single sticks as they are more profitable than selling whole packs. In 2019, a pack of 20 Sportsman cigarettes (the most popular discount cigarette brand) cost Ksh 150 whereas a single stick cost Ksh 10.Reports also indicate that stalls sell single cigarettes within a 250-meter radius of primary schools across the country, in violation of section 15(1) and section 16(1) of the Tobacco Control Act.

Roughly 80% of these stalls fail to post warning signs prohibiting the sale of cigarettes to people under the age of 18.The ban on marketing and consumption of shisha in 2017 was initially successful within Nairobi County.

However, media reports in 2022 indicate that shisha marketing and consumption is still occurring.Compliance With Shisha Ban by Area in Nairobi County

The use, import, production, sale/offer for sale, marketing, and distribution of shisha, as well as the encouragement or enablement of its use, were outlawed in Kenya in 2017.

A 2021 study done in Nairobi county showed initial compliance with the ban, with 82% of the locations visited being in compliance. Shisha smoking was observed in 17% of venues (restaurants, bars, and nightclubs), and shisha equipment was displayed in 2% of all places visited. Of the various venue types, 95% of restaurants, 80% of bars, and 76% of nightclubs were compliant with the ban.However, media reports in 2022 indicate that shisha equipment is now seen at bars and nightclubs in Nairobi, and shisha smoking is popular among socialites and sportspersons. Shisha is either sold by the club owner or by third parties allowed to sell to patrons (with profits shared with the club owners). Shisha equipment can also be ordered from online stores like Kilimall

as well as Facebook and Instagram; equipment can also be purchased from khat sellers in Eastleigh. Fruit-flavored brands are very popular and, depending on location, two to five friends can share a shisha pot for between KSh 500 and Ksh 3,500. The renormalization of shisha marketing and consumption is attributed to political interference with enforcement.